The Red Sift Blog

Red Sift ASM & Red Sift Certificates: the missing link in your CTEM strategy

Red Sift ASM & Red Sift Certificates: the missing link in your CTEM strategy

Filter all blogs

All blogs

Red Sift ASM & Red Sift Certificates: the missing link in your…

According to Gartner, Attack Surface Management (ASM) refers to the “processes, technology and managed services deployed to discover internet-facing enterprise assets and systems and associated exposures which include misconfigured public cloud services and servers.” This broad category of tooling is used within Continuous Threat Exposure Management (CTEM) programs, with many vendors within it having…

Read more

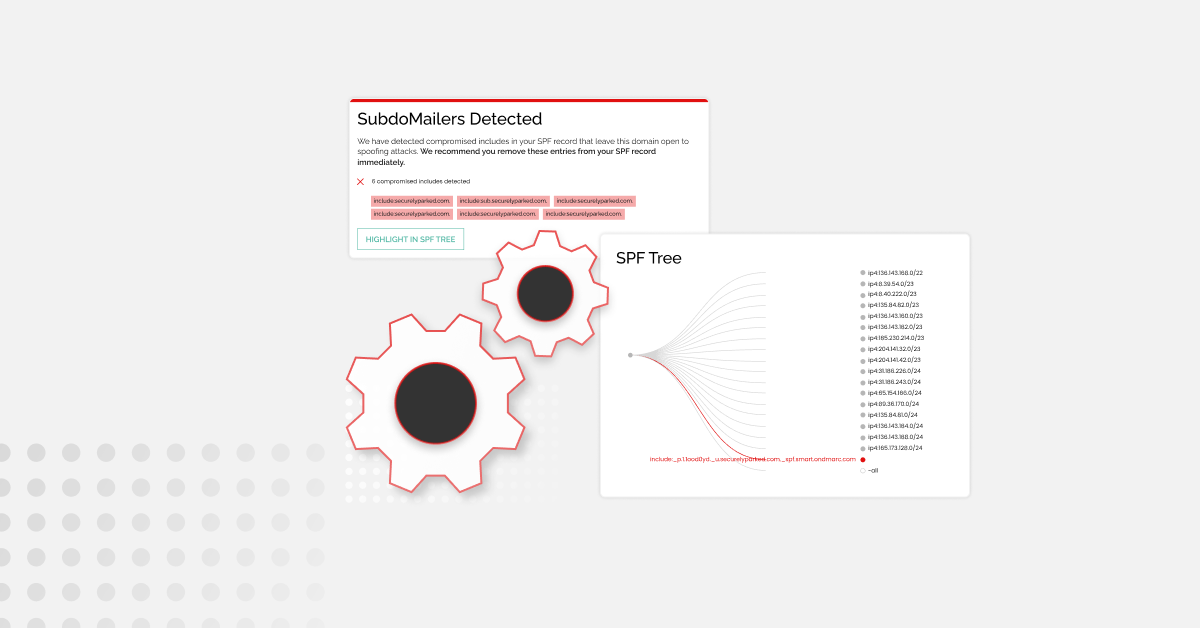

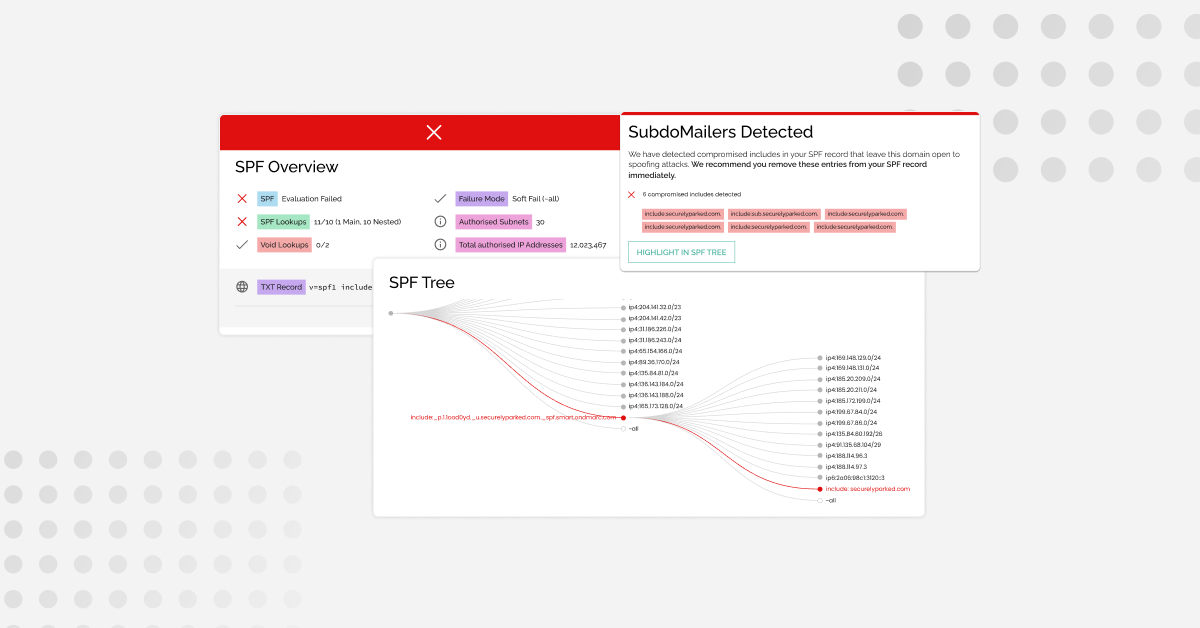

The best tools to protect yourself from SubdoMailing

In late February 2024, ‘SubdoMailing’ became a trending search term overnight. Research by Guardio Labs uncovered a massive-scale phishing campaign that had been going on since at least 2022. At the time of reporting, the campaign had sent 5 million emails a day from more than 8,000 compromised domains and 13,000 subdomains with several…

Read more

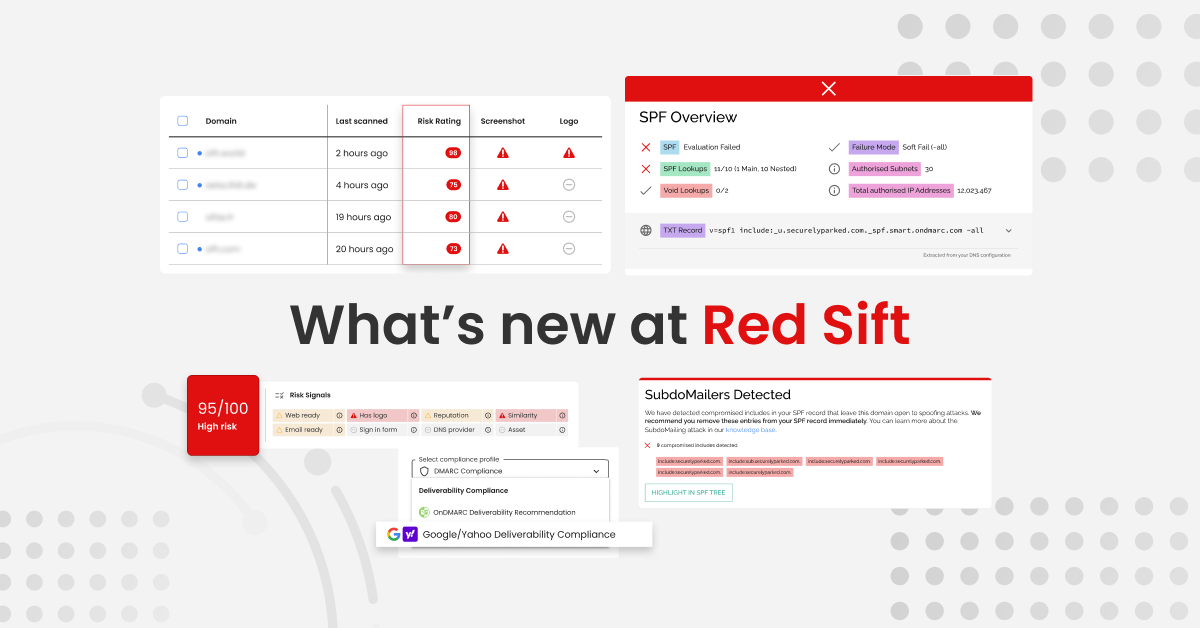

Red Sift’s Spring 2024 Quarterly Product Release

This early into 2024, the cybersecurity space is already buzzing with activity. Emerging standards, such as Google and Yahoo’s bulk sender requirements, mark a new era of compliance for businesses reliant on email communication. At the same time, the prevalence of sophisticated cyber threats, such as the SubdoMailing campaign, emphasizes the continual hurdles posed…

Read more

Navigating the “SubdoMailing” attack: How Red Sift proactively identified and remediated a…

In the world of cybersecurity, a new threat has emerged. Known as “SubdoMailing,” this new attack cunningly bypasses some of the safeguards that DMARC sets up to protect email integrity. In this blog we will focus on how the strategic investments we have made at Red Sift allowed us to discover and protect against…

Read more

Where are we now? One month of Google and Yahoo’s new requirements…

As of March 1, 2024, we are one month into Google and Yahoo’s new requirements for bulk senders. Before these requirements went live, we used Red Sift’s BIMI Radar to understand global readiness, and the picture wasn’t pretty. At the end of January 2024, one-third of global enterprises were bound to fail the new…

Read more

Your guide to the SubdoMailing campaign

A significant number of well-known organizations have been attacked as part of what’s being called the SubdoMailing (Subdo) campaign that has been going on since at least 2022, research by Guardio Labs has revealed. The scale of execution of this attack is staggering, and the impact is hugely damaging, but the goal is simple…

Read more

A confident deployment guide for TLS and PKI

Our journey to better network transport security has been quite the ride, filled with ups and downs. Back in the ’90s, when SSL and the Netscape browser were just taking off, things were pretty hard. We were dealing with weak encryption, export restrictions on cryptography, and computers that couldn’t keep up. But over the…

Read more

Red Sift OnDMARC: The best Agari alternative for DMARC

Looking for an alternative to Agari DMARC Protection that helps you safely and efficiently stop unauthorized use of your email-sending domains? You’re in the right place. Here is your definitive comparison guide for Agari and Red Sift OnDMARC – one of the most popular Agari alternatives on the market. Red Sift OnDMARC overview Red…

Read more

Red Sift OnDMARC: The best Valimail alternative for DMARC

Looking for an alternative to Valimail that helps you safely and efficiently stop unauthorized use of your email-sending domains? You’re in the right place. Here is your definitive comparison guide for Valimail and Red Sift OnDMARC – one of the most popular Valimail alternatives on the market. Red Sift OnDMARC overview Red Sift OnDMARC…

Read more

Announcing the beta for Red Sift Radar: An LLM Assistant for Security…

We are delighted to announce the beta for Red Sift Radar – our new LLM assistant for security teams. With Red Sift Radar, teams will be able to use an LLM to automate manual checks, drive security consistency, and build bridges with less technical teams. To bring this to life, we have taken base…

Read more

Navigating Corporate Risk and Cybersecurity: A Discussion with Annie Searle

By Sean Costigan, PhD In a recent exploration of the intricate world of corporate risk management and cybersecurity, I enjoyed the privilege of engaging in a compelling conversation with Annie Searle, a distinguished expert in the field of operational risk management. Searle’s extensive experience in the financial, IT, and emergency services sectors illuminates the…

Read more

Resilience Rising | Episode 1 with Annie Searle

In this episode of Resilience Rising listeners are invited to explore the complex world of cybersecurity and corporate risk with special guest Annie Searle. Annie will use her experience in operational risk management across the financial, IT and emergency services sectors to help risk and security leaders unpack their strategic challenges. The discussion delves…

Read more

February 1, 2024: A new era of email authentication begins

From today, Google and Yahoo are rolling out new requirements for bulk senders, ushering in a new era of email compliance. If you’re just learning about this now, here’s a quick summary: Google and Yahoo now require bulk senders – those who send more than or around 5,000 emails daily – to meet a…

Read more

How marketers can work with security to meet Google and Yahoo’s requirements

I am lucky enough to have been a marketer at multiple cybersecurity companies. From these roles, I have learned from some of the best in the business how to effectively partner with your security team on any initiative. Given that Google and Yahoo’s bulk sender requirements are imminent, it seemed like the perfect opportunity…

Read more

What marketers should know about Google and Yahoo’s requirements for bulk senders

From February 1, 2024, the world of email marketing is set to shift as Google and Yahoo’s requirements for bulk senders (businesses that send 5,000+ emails a day) come into effect. If you’re a marketer aiming to ensure consistent delivery to personal Google and Yahoo inboxes, it’s important you understand the upcoming changes and…

Read more

Why successful email marketing relies on domain authentication

How to master the essentials of email security for optimal campaign reach and inbox placement Crafting the perfect email marketing campaign is hard work. And, nothing is more frustrating than a perfectly crafted campaign not performing because the emails were delivered to the the spam folder. In 2023, Validity found that one in every…

Read more

2024: The year of DMARC as a business imperative

I can say with confidence that the world does not need more security predictions for 2024. But as we head into the new year, it is important to have conversations about security strategy to inform our business priorities and our road maps. As I talk to our Red Sift customers, our partners, and the…

Read more

Global mandates and guidance for DMARC 2024

For cybersecurity, email security and IT teams, understanding and adhering to global DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting, and Conformance) requirements is imperative. At Red Sift, we have put together a tabulated overview of DMARC mandates and guidance enforced across different regions worldwide. Our aim is to provide a clear, unambiguous guide that consolidates the…

Read more

Are you ready for Google & Yahoo’s bulk sending requirements?

Confused if your organization is ready for Google and Yahoo’s new requirements for bulk senders? I know the feeling. When the announcement came out in October, I was trying to figure out what they *actually* meant for people sending more than 5,000 emails a day. Luckily the team at Red Sift has helped prepare…

Read more

Certificate Monitoring versus Certificate Lifecycle Management

TLS certificates – once called SSL certificates and often referred to as just “certificates” – are one of the core ways we keep the internet safe and secure. Certificates encrypt data to make sure it is transmitted privately between your browser, the website you’re visiting, and the website server. But as the number of…

Read more